Joan M. Mas 2007. (Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.)

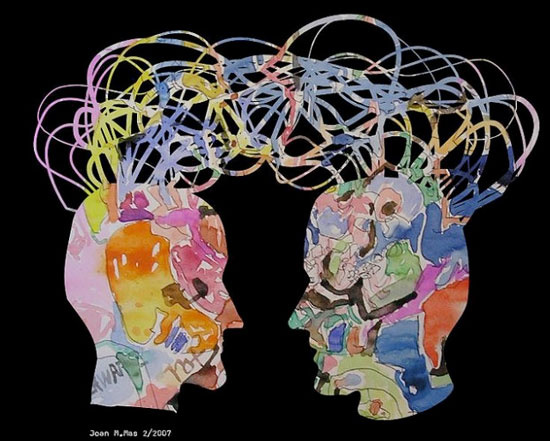

(VANCOUVER) Goethe's unhappy Faust, the archetypal lonely scholar shut away in his cloistered study, bears little resemblance to today’s “networked” scholar.

Of course, scholars have always communicated with others in their field. But until very recently their academic circle was based primarily on intellectual affinity and geographical proximity; conversations were largely face-to-face. Even scholars in the 1970s and 80s were decidedly low-tech, relying on snail mail to exchange research drafts with far-flung collaborators.

With the adoption of social media and mobile computing, scholars nowadays are increasingly tapping into much wider online social networks.

The change has been fueled by the growth and specialization of the academic world, which has left scholars finding fewer kindred spirits at their home universities. At the same time, their ability to encounter like-minded others is now greater than ever thanks to online networks and other communication tools that have unleashed an unprecedented power to create and share. Diversified and informal, these loose social networks allow them to keep on top of trends, collaborate, get advice, and disseminate findings.

Such modern shifts reflect a broader change within organizations, brought on by the global digital revolution, towards networked and distributed work. Mobile devices and computer networks – the new social networks – have seemingly overcome the spatial and temporal limits of the traditional workplace.

Networks of informal professional ties are replacing hierarchical structures and centralization. Divisions within organizations – the “silos” of traditional bureaucracies – have broken down to allow information to flow across departments, disciplines, and hierarchical levels. The aim: better innovation, collaboration, and knowledge transfer.

But how effective is networking?

To get real-world insight into this question, researchers in GRAND have turned their gaze inward, to GRAND itself, assessing its own effectiveness as a networked organization.

NAVEL-gazing

Launched through the Networks of Centres of Excellence program in January 2010, GRAND began as a loose network of academics, government and industry decision-makers, as well as other stakeholders. Its mandate: to maximize linkages across different disciplines and institutions engaged in digital media research. For example, the network’s geographically distributed teams span seven provinces with two-thirds of the research projects involving three or four disciplines.

One of those projects, NAVEL (Network Assessment and Validation of Effective Leadership), is GRAND’s self-reflective (“navel-gazing”) analysis of collaboration and communication among its community of scholars.

“We're studying both GRAND itself, and also how networked work operates. Our big question is how do people coordinate with each other when they are in multiple teams that may be spread across Canada (or any physical area) and in different occupations,” explained University of Toronto professor and project leader Dr. Barry Wellman. A pioneer of social network analysis, Dr. Wellman directs U of T’s interdisciplinary NetLab, which focuses on this area of sociological research and how ordinary people use digital media in their everyday lives.

In addition to surveys and interviews, NAVEL’s analysis draws upon researchers’ experiences captured using tools developed by its counterpart project: MEOW (Media Enabled Organizational Workflow), led by Dr. Eleni Stroulia at the University of Alberta. MEOW’s web-based software both manages and tracks GRAND’s network activity and encourages collaboration and exchange among its members. As well, NAVEL researcher Dr. Anatoliy Gruzd and his students at Dalhousie University's Social Media Lab actively contributed to the data collection, transcription, analyses, and presentation of the results.

"We're able to use GRAND as a laboratory of how people at a distance and from different disciplines work,” said Dr. Wellman. “Researchers turned out to be interesting because, like ball players, we have very good metrics on them.”

Following a two-year study, NAVEL published its findings in the January 2014 edition of Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Dr. Wellman and project manager Dr. Dimitrina Dimitrova (York University) led the study in collaboration with Dr. Anatoliy Gruzd and his students, and U of T PhD. students Zack Hayat, and Guang Ying Mo.

“Long-standing traditions of long-distance collaboration and networking make scholars a leading-edge test case for differentiating hype and reality in distributed, networked organizations,” states the report. “Despite widespread interest in networked organizations, there has been more speculation than evidence.”

"What we're finding gives us solid evidence for feeling that the turn to networks is a really good turn," added Dr. Wellman. "Our NAVEL team has been able to show that GRAND has made a difference in Canadian scholarship.”

The Scholar as Networked Individual

Dr. Wellman's recent research has been examining a societal shift away from the traditional closely-knit groups of families, neighbourhoods, or work groups towards loosely bound, sparsely knit, and fragmentary social networks. Dr. Wellman calls this “networked individualism,” and according to him, it is changing the rules of the game for social, economic, and personal success.

In their 2012 book Networked, authors Dr. Wellman and Lee Rainie (Director of the Pew Research Center's Internet and American Life Project) show how a technological “Triple Revolution” – the synergistic rise of the Internet, mobile technology and social networks – has transformed people’s relationships with each other and to information.

Impacted by this revolution, GRAND researchers also appear to be working as networked individuals, according to the findings of NAVEL and other projects directed by Dr. Wellman. Digital media has allowed scholars to maintain larger, more specialized, and more diversified networks. But in spite of the wider digital reach, they still tend to talk with the same people online as they do offline. In-person contact among GRAND scholars is used almost as frequently as email to keep in touch.

“Digital media provides the scholars with enhanced global connectivity with kindred colleagues, including increased visibility, access to specialized GRAND experts, and contact with prestigious senior faculty,” the report states. “Yet, it is the scholars’ in-person encounters as collaborators and conference-goers that create and maintain their online contacts.”

Not surprisingly, GRAND’s Annual Conference, an event where researchers bump into colleagues and discuss ideas or actual projects, plays a crucial part in their networking.

“Generally people like to be physically close to each other. When they see and smell and touch each other, they have a better ability to work at a distance later. That's why conferences, such as the GRAND conference, are really important,” said Dr. Wellman.

Proximity still counts. Scholars tend to work with others in the same metropolitan areas and universities. But they value their connections with other GRAND researchers at universities in distant parts of the country. Indeed, GRAND’s digital savvy researchers rarely connect with colleagues using Internet phones or social networking, but prefer travelling great distances to meet them in-person.

As for academic productivity, GRAND networking seems to have paid off. This is not only shown in increased publications and presentations, but also in the informal exchange and advice between colleagues. Collaborative tools and technologies were also a factor in more papers being coauthored within and across disciplines and geographic areas. As a follow-up report internal to GRAND summed up: "In a nutshell, better-connected researchers are more productive.”

The article does cite a number of downsides to digital media. It can increase misunderstanding, delay communication, decrease cultural acclimatization, and hinder trust, as compared with in-person communication. Cultural differences between disciplines can also impede a mutual understanding and collaboration of professionals. The best bet is a hybrid of digital and face-to-face communication.

The study also overturns popular assertions (for example, by MIT professor Sherry Turkle) that technology creates social isolation by replacing in-person encounters with online connections: “Rather than digital media luring people away from in-person contact, larger networks make more use of digital media, overall and per capita,” the study concludes.

It’s a finding that reaffirms Dr. Wellman’s continuing research into how ordinary people are networked individuals.

"There's a big fear that the world is falling apart, that community is dying, and that people aren't relating to each other as a result of the Internet. We find that the exact opposite is happening," said Dr. Wellman. The Internet is complementary to face-to-face contact.

On the turn to networked individualism by scholars, the NAVEL study ends on an optimistic note: “The benefits for a flexible social organization —and life—are palpable.”

For Dr. Wellman, the results will inform future studies of networked work and life.

"I really want to look at networked work more broadly than GRAND. We want to take this and look at more organizations in Canada and the U.S. and see how they actually work over distances, and what are some of the problems that they've had,” he said. “It's something a lot of people talk about and hardly anyone has any evidence on. And I would like to give them evidence on how network work works!"

-30-

Media Contact:

Spencer Rose

Communications Officer

GRAND NCE